The day my father drove us to the backwoods, he told my mother it was where God wanted us. He didn’t include himself in the word us—only my mother, her rotting lungs, and her seven living children.

I was three years old the morning we Woodard children piled into the borrowed pickup and headed through Oklahoma toward a flyspeck town called Lequire (Lee-quire). John Dean, Frank, and Clyde sat in the back. I felt thankful John Dean slept most the ride because even at the age of eleven, long before his schizophrenia diagnosis, it was clear that something was off. He bucked against orders and seemed driven by an inner demon. My dad showed no mercy for his differences and beat him often, along with my four-year-old brother, Allen Earl, who cried often and wet the bed.

I sat in the front seat between Becky, who competed with Baby Beverly for a spot on Momma’s arm, and Allen Earl, who squeezed my hand anytime our father screamed at other drivers racing past.

Bevel Woodard, or “Reverend” as some called Daddy, believed that speed was a trait of the devil. He taught us the traits of the devil from the moment we were born, so I already knew a thing or two. My big cousin Susan was headed to hell faster than a rat up a drainpipe because she wore trousers and lipstick. The folks who smoked in the church parking lot were hell-bound, too, along with those who danced or wore jewelry or took the Lord’s name in vain. All kinds of things could send you down there. It was alarming, and I grew up shaking.

Daddy’s speedometer danced around thirty miles per hour that day on the highway. Cars trailed us closely, and horns blared, which only made my father go slower to teach them a lesson. “Race on, you fools!” he roared out the window, waving his fist. “Hell ain’t half full yet!” Spit flew from his lips when he screamed. His small nostrils flared. He was five-foot-nine, hardly an inch taller than Momma, but I was certain Goliath would shrink in his presence.

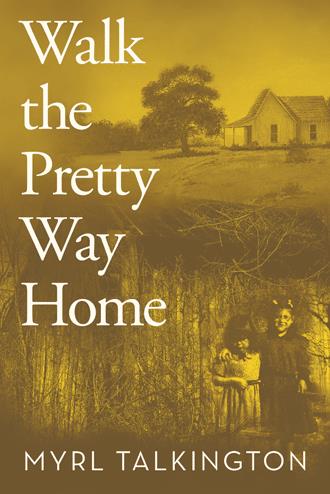

Our three-hour journey on the road to Lequire is one of my earliest memories. Before Daddy decided he needed to hide Momma from the city doctors, we lived in a small house in a lovely suburb called Sapulpa, twenty miles from Tulsa. Daddy sold the house but arranged to stay in Sapulpa in the back quarters of his shoe shop while we took lodge out in the sticks. Bevel Woodard was a cobbler by trade; a Pentecostal preacher by passion. He was in the business of soles and souls.

I don’t remember much about our Sapulpa house. It had electricity and running water, as any city home did in the fifties, but I didn’t realize to appreciate these commodities while I had them. Those were the glory days of my childhood, with a bathtub and a toilet that I soon forgot.

Mostly I remember the old backyard. A wrought iron table that my grandmother had painted white sat like a centerpiece in the overgrown yard, chipping under the sunlight. I liked the curlicue details of its legs, but I didn’t like the about-to-flake look of the paint.

“Stop that, Myrl!” Momma would yell when she caught me peeling the paint with my fingernails. Yelling would make her cough, and coughing would make her spit on the ground like a man. Her globs of mucus, green and eventually pink-tinged, glinted under the sun in the dirt bed by the side of the house. The coughing fits and the piles of glinting spit grew until one day, Daddy stuck a For Sale sign in the weeds of the front lawn. I knew we were moving because of Momma’s illness, but I didn’t understand why.

In the moving truck, I leaned over to Allen Earl, who was my closest playmate. I was going on four, and he was going on five.

“Allen?” I whispered. “Why’s we movin’ far away to a old farm house?”

Sweet, timid, Daddy-fearing Allen Earl pressed his lips against my ear to whisper, “Myrl, we’s goin cause’a Momma’s problem.”

“The cough?”

He nodded. “She’s got TB. That’s why she coughs and spits blood. She cain’t go to the doctor cause Daddy says they’re from the devil.”

“I know that. But what’s TB?”

“I don’t know, and Momma said don’t ask again.”

Don’t ask – don’t even talk. That was the Woodard rule.