Chapter 3 – Setting the Stage

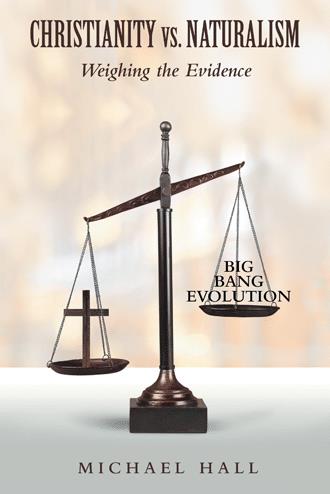

The two worldviews that are explored in this book are:

1. Our world came about through natural means starting with the Big Bang, creation of life, millions of years of evolution (slow changes over time creating a new species through mutation), that give us the world as we observe it today; and

2. Our world was created by the Biblical God. Unless we can articulate a scientific theory for the Biblical God, we cannot test it against the empirical evidence. There are two claims that most Christians’ acknowledge:

a. The Bible is the Word of God.

b. This God is omnipotent (all-powerful) and omniscient (all-knowing).

The Bible has many other attributes for the Biblical God, but they can only be evaluated through the lens (i.e., the acceptance) of the Bible’s validity. Thus, all other attributes of the Biblical God are outside of the scope of this book. A few other religions will also be explored, along with their ability to guide one’s life and actions. But there are too many religions in this world to attempt to cover them in any one book, so only four alternative religions will be discussed, and the discussions will be brief.

Chapter 4 – Introduction to Naturalism

Naturalism is a worldview that holds that the world we observe today came into being through natural means, rather than a supernatural being. It is based upon five major tenets: the natural origins for the universe, the natural origins for life, the evolution of that early life into today’s diversity of life, this evolutionary process took millions of years to occur, and there were many transitional steps between the first life and today’s diversity of life. The undergirding of this worldview is that these concepts can be postulated as scientific theories and can be subsequently proven true or false. They acknowledge that some of these theories will be proven false and subsequently replaced by new, testable theories to guide them to the final answer.

Most people believe that scientific theories are postulated, tested, verified, peer reviewed and then the findings are published in the media when the results would be of interest to the public. Nothing could be further from the truth. Hundreds of years ago, before the information age, that may have been true. But in today’s information age, as soon as a scientist reaches a conclusion supporting the scientist’s viewpoint, the findings are published in a publication with little to no peer-review process conducted and are often announced in the major news media for their readers’ consumption.

The reason the process works this way is all about money. The scientist gets funding from some source, and if the scientist does not produce satisfactory results within a reasonable amount of time, they lose their funding (i.e., no job). This encourages publishing early, non-peer reviewed conclusions. Often, many of these conclusions are subsequently proven false (i.e., falsified) by other scientists. But since the media is less interested in the latter conclusions, they are not usually published in places where the public has access to them. The public is left with the belief that science is finding new things out all the time and the scientific method is at work keeping the falsehoods out of the public’s eye. But let us look at how the scientific method is supposed to work and how it does work, and a real-life example in today’s information age.

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a process to find true knowledge. In its pure form, it does not care which direction the researcher desires to go. All that matters is that the research is: 1) Testable; 2) Supported with empirical evidence; 3) Can be reviewed and tested by other researchers; and 4) That it can be falsified if research finds empirical evidence that contradicts the original theory. Many people don’t understand the difference between a scientific theory and a scientific research program—and there is a major difference between the two terms.

A research program is a group of scientific theories, with each theory able to be falsified while the program itself is almost impossible to be falsified through any empirical evidence. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a “programme” (the British spelling of program) as “to predetermine the thinking, behavior, or operations of as if by computer programming.”

Research Programs

According to Imre Lakatos (1922–1974), a Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science, there are two types of scientific research programs, progressive and degenerative. In a progressive research program, the theory leads to new facts. In a degenerative research program, it either fails to predict new facts or has those predictions systematically falsified. However, Naturalists would rather have a degenerative research program “than to sit down in undeluded ignorance.” Thus, even a failing research program is better than no program advocating for a natural origin for the world that we see today.

“Does this mean that no research programme should be given up in the absence of a progressive alternative, no matter how degenerate it may be? If so, this amounts to the radically anti-sceptical thesis that it is better to subscribe to a theory that bears all the hallmarks of falsehood . . . than to sit down in undeluded ignorance.”

So, even if every one of Naturalism’s tenets fall into a degenerative research program, they are content to continue down that path rather than falsify any of the necessary tenets need for a belief in Naturalism. Why is this true? Most scientists today subscribe to Lakatos’ concept of science.

“[F]alsifiability continues to play a part in Lakatos’s conception of science but its importance is somewhat diminished. Instead of an individual falsifiable theory which ought to be rejected as soon as it is refuted, we have a sequence of falsifiable theories characterized by shared a hard core of central theses that are deemed irrefutable—or, at least, refutation-resistant—by methodological fiat. This sequence of theories constitutes a research programme.