I am a child of the High Plains. My childhood memories hearken back to scorching July winds, black thunderstorms on the horizon, and fields of golden, waving wheat—clichés, all of them, but realities nonetheless. I also remember loneliness. Thus I left rural Northwest Kansas in 1989 to attend the University of Chicago, glad to finally begin my life, put that desolation in the rearview mirror, and see the country—or so I thought. Well, with my wife and sons along for the mad ride, we have trekked from one coast of this nation to the other courtesy of the US Navy. We have lived in eight states and seen the sights and cultures of America’s North, South, East, and West. Having slept under a wandering star for so long, why do I find my thoughts so frequently returning to that dusty corner of Kansas I was so eager to leave behind? Only now, more than thirty years after departing, I begin to comprehend how my dry, windy, isolated upbringing shaped who I am and how I see the people and the world around me.

These stories are my exercises in self-reflection, the inevitable inner ponderings that come as we age. For most, musings about days gone by don’t lead to written stories, but for someone not terribly adept at expressing thoughts and emotions with the spoken word, perhaps this form is my best outlet, even if indulging family members are the only ones who ever read my ramblings. Maybe the proper course would have been a long letter to my children. At least it might help them understand what makes the old man tick. They may offer, “But hey, Dad, let’s keep it in the family where it belongs, like other normal and unpretentious folks.” What, then, prompts me to believe someone outside my family circle would ever want to read this? Truthfully, I don’t know whether anyone ever will, but a chorus of thinkers and writers are striving to discern the heart of our nation, and I would like to add to that song. My small voice, somewhere over in the back row of the tenor section, singing about the contributions of the plains and, more importantly, their people, will, I hope, be a useful addition to our choir of national self-consideration. We all have much to contemplate.

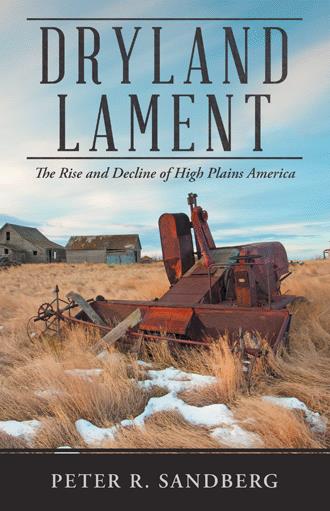

This undertaking started as a jumble of childhood memories, stirred in together with a sense of sadness and loss. Those feelings were with me even as a child. Standing in front of the decaying outbuildings on my grandparents’ eastern Colorado farmstead, I felt a pervading sense of what might have been. A few hours east, closer to my boyhood Kansas home, the countryside was also dotted with abandoned homesteads, usually marked by a few defiant cedar or elm trees jutting from the corner of a field, sometimes accompanied by a desiccated wooden skeleton of an old farmhouse or barn.

Early in my youth, I realized the place where I lived was, in a real sense, dying. Juxtapose that with the sometimes difficult but remarkable people around me. They worked hard, so why was this happening? It seemed that the best efforts of generations could not stave off decline and failure. I could not shake a foreboding. Our community labored on, but everyone knew the prairies were slowly emptying. While this fact was oft remarked upon, the spirit was not one of grumbling, but more of abiding sorrow. I return continually to the word “lament.” Too strong? At its most basic, a lament is an expression of sorrow or grief, so perhaps sorrow is warranted, but grief? Really? That seems a bit much. I humbly ask the reader to bear with me, for lament is both biblical and purpose-filled. And yes, I do feel a sense of lingering grief about what America, the Great Plains, and even my family have lost over the previous one-hundred-plus years. We plains folk reserve the right to use that word.

Hoping to better understand the history of the Great Plains, I have spent years as a novice reading academic works, articles, and reports about the region. However, I am not thus a historian, and this is no attempt at a scholarly tome. Libraries are already filled with first-rate historical works explaining the geographic, climatological, economic, technological, social, legal, and other forces at work shaping life on the Great Plains. I’m happy to draw from the efforts of authors and academicians without attempting to replicate or improve the historical record. I care most about the people of the plains: who they were, who they are, and what their experiences mean to this nation’s past and future.

Over twenty years ago, Kathleen Norris, in her book Dakota, A Spiritual Geography, wrote, “The children and grandchildren of farm people forced off their land today may well be the ones to write about it. Perhaps given the distance that the passage of time can provide, they will give us back the truth about ourselves. Whether or not we will listen, out here on the Plains, I cannot say.” She could give herself more credit. Norris herself has already painted dramatic word pictures to help explain the realities of prairie life, but she is nevertheless still correct; there is more to be said.

While any single attempt to capture the sense and spirit of an entire region will inevitably fall short, in the spirit of Norris, my small porch light shining onto prairie life may yet help illuminate larger forces at work in our country. Certainly, one individual’s memories harvested during a childhood spent in an old, yellow wind-rattled farmhouse on a Kansas hilltop won’t convey the deep-rooted connections that rural people feel with their surroundings, or the pain of successive cycles of planting, waiting, harvest, and then winter and death that have shaped High Plains inhabitants.