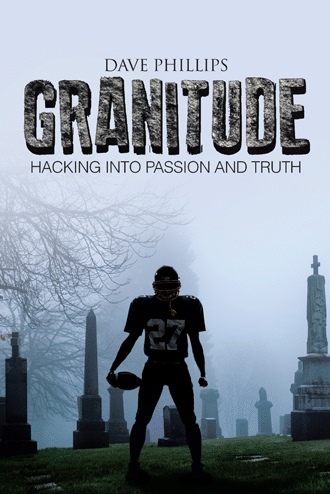

Granitude

Of Granite

Etched in stone,

We expire alone.

Carve more the day,

We know The Way.

chapter one

“Josh Hanes is not getting up!” crackled the stadium speakers. “He’s one stride short of the goal line.” The announcer paused. “Folks, he’s going to need some help … okay, the coach and trainer are jogging over to help.

“That was a tremendous hit Hanes took by Southpoint’s all-conference tackle Phil Hernandez. But he might have been hurt more by big number twenty-three, Shawn Warfield. Warfield, tipping the scales at three hundred and twenty pounds, was first on the pileup after Hernandez dropped him. There seems to be no movement from Josh. He really had his bell rung, folks.”

Josh heard the announcer and the voices around him. A few teammates were on their knees asking if he was okay.

He didn’t know if he was okay. He took a hard bounce on his stomach and chin, with arms outstretched for the goal line. His neck and shoulders hurt. His chin was sore. His chest swelled as slowly as senile memory foam, straining to breathe after the fat kid climbed off of his back. Tiny electric stars darted past his forehead, like a current of wind-driven snowflakes breaking around the windshield of his car. The world was out of focus until he heard her voice.

“Josh, oh, honey! It’s me, honey—Cindy. Josh, can you hear me?”

Her perfume gave him strength, a reason to gather himself. She was there by his face, on the ground with him, coming into focus. The stars yielded to her angelic face. She was more perfect than he remembered. Maybe he’d never looked up at her from that angle. Her sandy hair fell like soft waterfalls to the ground, framing her pretty, tan face. Her eyes were China blue, her nose and cheeks thin. She had a permanent dimple a thumb’s width from the corner of her smile. She was the best-looking girl in school.

Cindy reached down and kissed him high on his cheek. His helmet was gone. He was lying facedown on a sunny ocean beach with his beautiful girlfriend.

He lifted his head. His neck and chin still hurt from leaning over on the table. His arms tingled from pillow duty. He’d been so soundly asleep that his fogged brain thought he was somewhere else, like waking up in a hotel bed and, for a moment, thinking you’re home. The table he leaned away from was blond, just like his student desk at home. He was in the library basement. A second table was lined up with his end-to-end between two rows of floor-to-ceiling shelves in the partial basement. A hint of old dust filled the air. The shelves contained various brown-covered books stacked lying down, as if they were too old to stand up. Other books with faded amber, crimson, and olive covers stood upright just fine. A mixture of daylight from a window well and fluorescent tubes brightened the room. He faintly heard his own breathing. He was all alone.

The table was clean except for a hardback book lying facedown at arm’s length to his right. He sniffed, rolled his head back, and yawned. He reached for the ceiling, rolling his wrists, clenching and stretching his fingers in turn. His butt and legs felt as wooden as the chair he was sitting on.

He pushed to his feet and fished his cell phone from his pocket. He noticed a missed call from Cindy and a text message.

Her text read, “Don’t text back. Dad didn’t ground me … YET! Sorry he was such a butt … you ok? Miss you. Love you! I’ll call sometime don’t call me!”

The message drove him nuts. He really wanted to be with Cindy. This whole situation was making him crazy. He couldn’t take the risk of calling or texting. He would have to wait for her to call again. He punched up vibrate mode on his phone, regretting the earlier move to go all silent.

Cindy’s text triggered his memory of the blowup with her dad that morning. He shrunk back into the chair and stared across the shiny library table. The scene replayed in his mind, indelible, like a DVD movie.

* * *

“Really! You just walked out! Didn’t tell management? You just left? Is your middle name Loser?” demanded Shag, Cindy’s dad. His head was a purple cabbage, with boiling blue eyes. His neck swelled with bulging red veins.

Josh said nothing.

Cindy’s dad wasn’t a known hothead, but he was clearly upset when Josh showed up late that morning to wring a bit of sympathy from Cindy.

“You have the gall to show up here asking for my daughter after walking out on a perfectly good job? You irresponsible little punk!” Shag flailed his right arm, alternately shaking and pointing.

Josh didn’t know what gall meant, but it sounded enough like ball to make him think Shag meant balls. Didn’t matter. The words didn’t matter. Josh had just experienced his first real dressing-down in his young life. An uncomfortable cocktail of embarrassment and tension wrapped him up. Cindy’s dad had paralyzed him. His knees were weak.

Cindy appeared halfway down the staircase and sat down, clutching a banister spindle. Josh stole a glance at her, but her dad was his whole life at that moment. Josh needed to run away, as he’d done with his job only an hour before. Somehow running away from a lecture about running away was not physically possible. He trembled like a prisoner in chains, ready for the next lashing.

Instead, only a lung full of scold away from turning physical, Shag relaxed his shoulders. His eyes softened with a hint of compassion. Josh relaxed his fists at his side with the slight reprieve. It was a new flavor of embarrassment for Josh, laced with empathy, making him feel awkward.

Josh didn’t want to tangle with Cindy’s dad in front of her. He would lose, whatever the outcome. Besides, at more than double Josh’s age, Shag was stocky and intimidating. He’d been a hotshot catcher in school. Professional baseball scouts had been spotted at a few of his high school games. His talent was catching uncatchable pop fouls behind the plate. His real name was Jim Hester, but they called him Shag because he was like a behind-the-base fielder. The Pittsburgh Pirates invited him to tryouts the summer after graduation, but his throw to second base was three-hundredths of a second too slow for the pros. Several colleges called, but Shag was more interested in getting a job and a car. He was not convinced that four years of college would shave three-hundredths off his throw to second. Besides, working that hard for three-hundredths of a second took the fun out of baseball. Shag was still a celebrity of sorts for those who remembered the fancy pro scouts thirty years earlier. He had a fun nickname and a rep. It didn’t take much to be large in a small town.

Shag measured his words. “Look, Josh, I like you. I think you’re basically a good kid, but you’re gonna have to buckle down and learn how to work. How to value a job. How to be responsible. And how to have enough respect for the company who gives you a paycheck that you give them proper notice when you’re going to quit!” Then he was angry all over again. Like a hot-water faucet, he warmed up as he poured it on. Compassion turned to ire in his eyes.

“You’re grounded from seeing Cindy! You’re grounded from all forms of communication with her. I’ll check her cell phone records. If I even suspect you two are texting or talking—through Facebook, tweeter, whatever—it will be a permanent grounding!”

Shag was old school and not likely sharp enough electronically to cover all possible ways teenagers talked if they wanted to. However, Josh had enough crazy love for Cindy that he was not about to risk challenging Shag.

“And one more thing”—Shag moved into Josh’s space with a pointed finger—“you need to push reset on your whole approach to life.” Shag poked him once, hard in the chest, rattling him against the storm door. “You’ve gone off the rails, young man. My daughter will not date a loser. Now get out of here.”