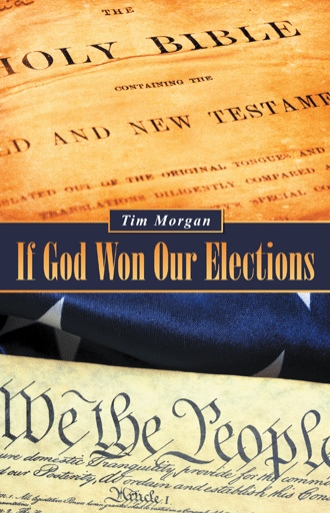

Every year, with the “bonfires and illuminations” John Adams suggested, we celebrate the day when this nation declared itself to exist under a government to which the governed give their consent. The electorate gives that consent by making, at regular intervals, a pilgrimage to the polls, which is preceded by months of speculation about who will win that election: who’s ahead, who’s behind, and who will have the upper hand in the end. I invite you now to consider a far more significant possibility. What if God won our elections? One may say God is never on the ballot. Officially, of course, that’s true. But spiritually, God is always on the ballot wherever voters have a free and genuine choice. The question before them on Election Day is the same one Joshua put to his people over three thousand years ago: “choose for yourselves today whom you will serve” (Joshua 24:15). Will we choose leaders to serve us because they belong to our preferred political party or pledge to pursue what we think is in our personal interests? Or will we choose leaders who answer Joshua’s question the way he did: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord”? What sort of a country would we have if we were to choose such leaders? Some say we would have something unconstitutional. If God won the election because the electorate chose to elect those who serve God, that would be an establishment of religion by the state—a profound evil. More than a half century ago, the US Supreme Court issued its ruling banning prayer in the public schools; since then, it has been illegal for public school employees to pray out loud with their students. This too has been declared an establishment of religion by the state. There are still many children across America whose school days start by saying the Pledge of Allegiance. Complaints have, so far, failed to reach the Supreme Court, but we’ve probably not heard the last of attempts to make two words in that pledge illegal for our public school students to say. You know which two: under God. This is the point to which that court ruling over fifty years ago has brought us: a public employee may not speak aloud the words under God in the presence of children at school without being accused of establishing a state religion. Did our national founders, when they wrote the Bill of Rights, really mean saying the word God out loud would create an establishment of religion? Can any reasonable person claim that’s what they meant? The founders never explained what they meant because the definition was supplied by the time in which they lived. The colonists who had emigrated to America had mostly done so from countries in which one’s nationality determined one’s religion. If you were born Swedish, you were Lutheran; if you were born Spanish, you were Roman Catholic; if you were born English, you were Anglican; and if you were born Scottish, you were Presbyterian. If you tried to follow some religion other than the one you were born into, you were in trouble —going to prison kind of trouble; going to the rack and the gallows kind of trouble. Our ancestors came here, in part, to get away from that kind of trouble. But that doesn’t mean they were ready to let people establish any sort of religion they wanted. They sought freedom for themselves but not necessarily for people with different opinions. The early colonists who came to America for religious reasons came because they thought they could have the established religion here be their religion. As soon as they got away from the state religions in their old countries, they set up state religions of their own. The laws they promulgated varied from colony to colony and, later, from state to state. But, commonly, church membership was required in order to vote and hold public office. Church attendance was required, and lack of attendance resulted in a fine. There was a government-approved creed, and if anyone publically taught anything else he or she went to jail. Only clergy licensed by the government could preach or administer the sacraments. Non-official churches could not own or sell property. The established denomination put up church buildings and paid its clergy with tax money. This was the establishment of religion the founders meant. A religion was established in a way that required legal penalties for refusing to participate in it or pay for it and for preferring other religions in its place. The issues the founders sought to prevent regarding religion and the state were not issues that might happen but those that had already happened. They were responding to objections that had been raised in response to actual events. Therefore, the founders could not have meant to silence audible prayers on public properties or on occasions when no one is required to join in. They could not have meant to prohibit a public official from expressing a religious opinion or proposing action based on that opinion. They could not have meant to stop all things religious from being said or done where a non-religious person might hear or see. They could not have meant to ban prayer in publically owned schools if there is no penalty for not praying and no added cost to the taxpayer associated with the prayers. If God won our elections, our leaders would seek God’s guidance and take God’s counsel as our fathers from Abraham to Lincoln have done. If God won our elections, our leaders would openly appeal to God in prayer and rely on God for our protection as the founders declared and relied on. If God won our elections, we would be safe from any attempt to substitute counterfeit rights for the genuine and natural rights our Creator endowed us with. Finally, if God won our elections, little children, even in our schools, could again say, “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord!” and it would never be illegal - as we pray it never will - to teach children we are the nation the Declaration of Independence and the blood of fallen heroes has made us; one nation under God.